How to mainstream impact investing

The world is on track to meet only 15 per cent of the UN sustainable development goals, says Impact Europe.

Politicians should put impact at the centre of EU policies to “accelerate the transition to a more innovative, sustainable and inclusive economy”. This is the message of a manifesto launched by Impact Europe — a network of foundations, impact funds, financial institutions and public funders whose members include companies such as Danone, BNP Paribas Wealth Management, Société Générale and Allianz — in the European Parliament this morning, ahead of the June elections.

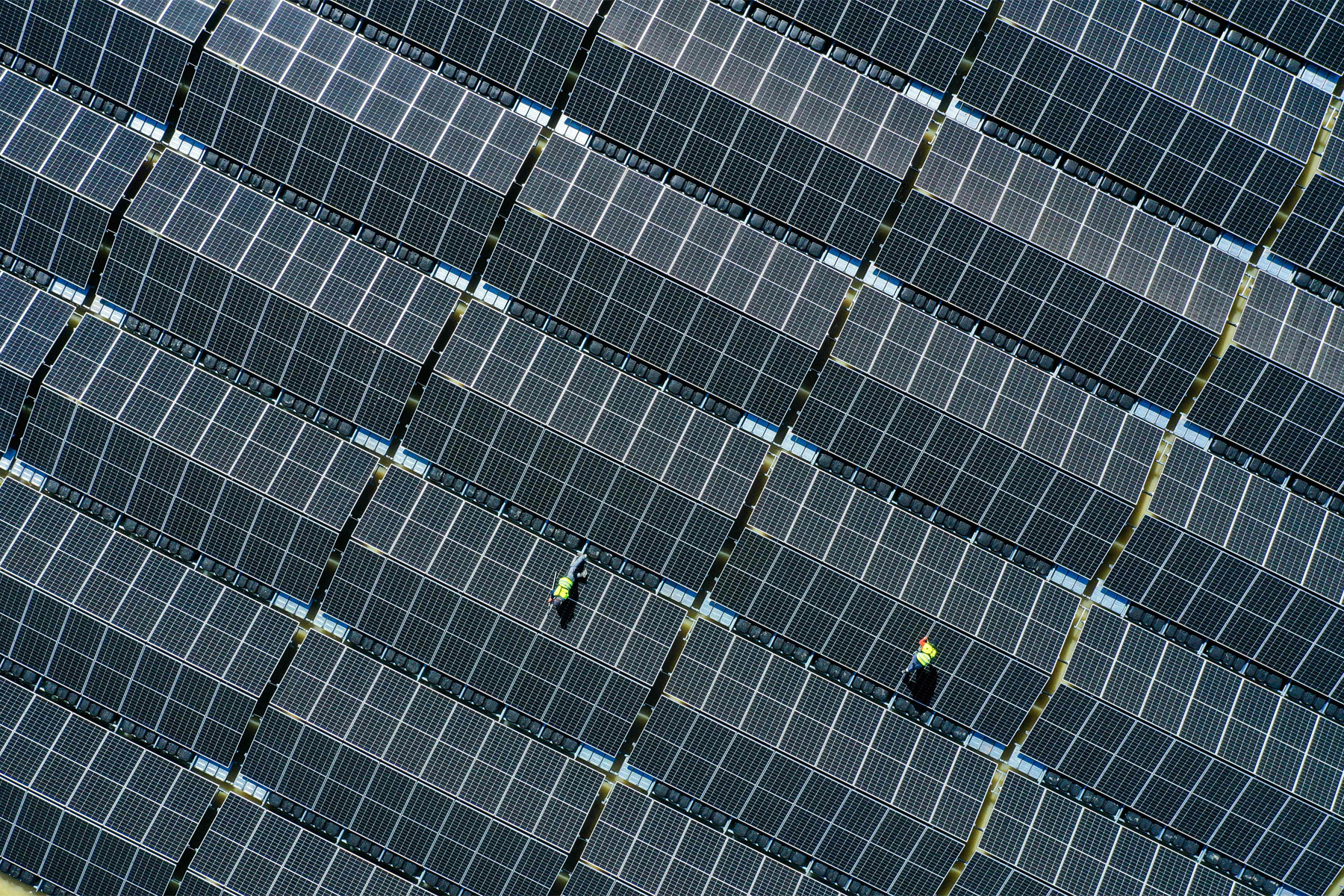

“A just transition to a green economy can’t happen unless impact investors step up,” says Roberta Bosurgi, CEO of Impact Europe, calling for EU policymakers to enable the work of impact investors. “The stakes are high and now is the moment to drive transformative policies.”

The world is on track to meet only 15 per cent of the UN sustainable development goals, while “the urgency to act against climate change and rising inequalities has never been more acute”, says the manifesto. “Impact investing has become one of the fastest growing areas of investment” and “all investors have the potential to become impact investors”, it adds, but insists a favourable policy framework is needed for impact investing to hit €1tn in Europe by 2034 and to grow its mainstream market share to 10 per cent from 1 per cent. The market is estimated to have reached €80bn in 2022.

Impact investing market growth is driven by countries, such as France and the Netherlands, with favourable regulations, it argues, where governments have “democratised access to impact investment and mobilised significant resources from retail investors, who are increasingly demanding sustainable and impact opportunities”.

Among the network’s calls for action is a demand to put impact at the heart of EU sustainable finance policies. “It is time for Europe’s regulatory framework to distinguish between investment strategies for investing in sustainable activities (largely avoiding harmful practices) and those intentionally seeking a positive social or environmental impact,” says the manifesto.

Such a framework, it suggests, could include: labelling schemes, with an impact category in the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation; “simple disclosure rules” for all financial products addressing environmental and social factors under the SFDR; and a strengthened double materiality principle in the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive with “harmonised impact measurement and management” incorporated in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards.

More generally, the manifesto calls for people to be put at the centre of green transition policies to ensure change is “inclusive and equitable”. A more just transition could be achieved if investors had a social investment framework and at least 10 per cent of public funding were allocated for social impact, it argues.

It seems doubtful the next set of MEPs is likely to be particularly receptive to such plans if, as expected, the parliament moves further right and has a higher percentage of politicians pushing for less, not more, frameworks and regulation. Any idea, though, that policymakers will backtrack on reporting is highly unlikely, Fiona Melrose, head of group strategy and ESG at UniCredit, tells me.

“The train has left the station when it comes to reporting for the largest companies. There is increasing awareness this needs to be front and centre of the work of financial institutions,” though a “lack of consistent data”, in particular around biodiversity, is making reporting efforts more difficult, says Melrose. “The CSRD will lead to more public data, but there is no one-size-fits-all way to ensure the necessary data for reporting is available. There are lots of moving parts and each industry has different variables.”

A coalition of nonprofits and academics, meanwhile, suggests the EU should do more to reduce the material footprint of companies and individuals. It wants the European Commission to propose a law setting a binding target to reduce the EU’s raw material consumption to 5 tonnes a head by 2050, compared with 14.8 tonnes in 2022. The coalition says it favours an economic model embedding “qualitative and inclusive growth” instead of an economy based on the use of raw materials and energy to further growth for growth’s sake.

In today’s opinion, experts from the Centre on Regulation in Europe argue energy network regulators should be dynamic to better manage net zero challenges, and highlight their preference for “responsive regulation” — “a middle ground between the two extremes of regulation that relies on strict rewards or punishment in the form of laws and courts on the one hand, and laissez-faire or self-regulation on the other”.

*

This article was first published on FT's Sustainable Views.